TecC 15 - Imperishable Fame or Immeasurable Impact? The Ultimate Integration

When separate streams of progress combine and converge to reshape the entire landscape and leave a lasting echo [Longread]

This is a journey exploring human innovation, progress and achievement taking a first-principles approach. Over the last dozen or so episodes, I have chronicled, starting right from the start, this progress, taking a new approach blending both artefactual and institutional development that I’m calling technocentric - in the broad sense of associating the Greek word ‘techno-’ with innovation. In particular over the last 3 episodes we have picked up speed, one might say, looking at ever-more impactful and foundational breakthroughs - the domestication of the horse, the invention of the wheel and with other related achievements the beginning of the Bronze Age.

I now intend to put all these things together, in a slightly longer episode, as part of a consolidated and integrated case study of what promises to be one of the, if not the most outstanding story of human innovation, progress and achievements in pre-history. Grab yourself a few pots of coffee or a samovar of tea and let’s get galloping!

As has been my express intent, and has been amply demonstrated I trust, this has been a series blending a multitude of disciplines, straddling the conventional divides of the arts and the sciences and more concretely humanities and technology. In this article, I intend to briefly demonstrate the application of the rigor of the scientific method, in a simple and easy manner accessible to and usable by even the most non-technical and untrained non-specialists, as part of fulfilling the above promise, and as part of showcasing my own approach in my cross-disciplinary endeavor. And of course I’ll be starting from scratch.

Mud-free Digging

And let’s start right at the beginning! It’s February the 2nd, 1786, and William Jones, a prodigious polyglot, philologist and judge in British India, speaking at the ‘Asiatick’ Society of Calcutta, makes this pronouncement:

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and forms of grammar, than possibly could have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason… for supposing that both the Gothick and the Celtick… had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

This of course astonished most people of the day as it would many today, given the sheer breadth of time and space of the languages and related phenomena alluded to in his declaration. But this seminal moment can be said to have led to the birth of the modern science1 of Linguistics, specifically Comparative Linguistics, which will not only definitively prove the core premise of his perspicacious and bold claim, but uncover a whole many more gems along the way, thanks to the rigor of the scientific method.2

Comparative Linguistics, or Historical Linguistics as it may more broadly be called, set out to evaluate Jones’s bold claim, by digging into the remote past of language. And I’ll give you a small glimpse of how this might work because, in line with what I said, it’s far more practicable for you and me to carry out, both without taking time away from our day-to-day jobs and commitments and without fancy or expensive equipment, compared to either archeology, which might explain what King Tut had packed as part of the Pharaoh’s paraphernalia into the afterlife, or using ancient fossils to reconstruct animals long dead before humans even got to the scene, the dinosaurs of course!

In addition, this scientific, if you like, game of what I call verbal archeology, carry-outable wholly here online, is a lot more fun than spending 3 weeks kneeling on dust and sand rubbing a toothbrush on the soil 8 hours a day to finally unearth a Neanderthal’s pinky finger bone fossil!

So let’s get started. You only have to put on metaphorical lab coats and pull out virtual Petri dishes and Bunsen burners - since this scientific experiment dwells not in the physical but the purely informatic (or digital) realm! And once you get a hang of this, even as you’re walking down the street or having a shower or something else, your brain will start to throw up these hitherto-never-thought-about connections, sudden dig-ups in your head of verbal archeological finds, connections between words, in a very satisfying process I call ‘wordgasms’!

A Common Home

The foundational scientific tenets are that language is fundamentally a spoken phenomenon,3 is passed on orally from generation to generation, and that over time, language inevitably changes. The changes are primarily in the sounds, owing to such oral transmission, but eventually also in word forms, structure and so on.

A core premise of the above pronouncement is the ‘springing from a common source’. In essence once a group of speakers split into two areas, over time the mentioned forces of language change, combined with decrease or complete loss of contact and mutual exchange, leads their forms of language to diverge into different dialects. We know this from experience, say the differences between what we call British English and American English, perhaps the easiest example to give - is 📱MOH-bl or mə-BYL?

And unlike in this transatlantic case, if the loss of contact is significant enough or even permanent, over time, these dialects become mutually unintelligible leading to what we may then call distinct languages. The best attested historical record of this phenomenon is the split of Latin into what we call Romance (ie, Roman) languages after the end of the Roman Empire, where over a few centuries speakers of (Late and colloquial) Latin across regions of the former empire such as Gaul (France), Iberia (Spain, Portugal) and Italy itself underwent such contact-loss divergences.

You can thus, using techniques afforded by Comparative Linguistics, deduce that Spanish ‘hombre’, French ‘homme’ and Italian ‘uomo’ have a common origin, in the Latin word ‘homo’ (as in ‘homo sapiens’), along with the realization that the descendant words might have undergone a slight (or sometimes large) shift in meaning. In this example, the semantic shift is not large and easy to see: the Latin word meant ‘human’ whereas these Romance words typically mean specifically ‘male’.4

Now apply such a phenomenon of linguistic divergence and evolution to a time period spanning 5000 years and you’ll see that such changes over such a larger period would be even bigger, so much so that, besides being harder to spot them without some clever methods, we find more than one ‘generation’ of such linguistic evolution - Latin to the Romance being only a single generation.

So I hope you’re now starting to make some sense of the claim by William Jones about this common source. Applying the scientific methods I’ve very very briefly hinted on, it has been proven categorically that the languages or language families he mentions, such as Sanskrit, Greek, Latin, Persian; Celtic, Gothic, and indeed many others he didn’t mention or wasn’t sure of, including Slavic (Russian, Polish etc), Lithuanian and English itself do derive from this single common original language.

If you still think this is unlikely, consider this just one of many such cases: almost every language within this wider family has two forms of that core existential verb: be/is. Here are just a few ones: Sanskrit: ‘bhu-’/’asti’, German: ‘bin’/’ist’, Slavic ‘by-’/’est’, Latin: ‘fu-’/’est’.5 Coincidence?

But how is it even possible, who were these people who spoke this common language, what was it called? Refill your cuppa and read on!

PIE in the Sky!

As a result of the investigations, detailed, meticulous and intensely argued about by scholars, in the domain of the science6 of Comparative Linguistics that kicked off in earnest in the early 1800s, this common parent language has been termed Proto-Indo-European (PIE for short), which represents roughly the geographic breadth of its spread to the continents of Europe and India, with ‘proto’ referring to its early, embryonic or pristine stage, and its unattested nature.

But you might still be itching to know, okay these fancy words or word changes are all well and good, but how did it actually all happen. And that’s understandable, since what I’ve mentioned is only a speck on a grain of rice on the tip of the iceberg! This is where all this ties in to the 3 previous episodes which have been building up the foundations of the theme of this episode.

I started that trilogy with the story of the domestication of the horse, after which we discussed the wheel, followed by a broader treatment of the technological developments that ushered in the Bronze Age.

Around the year 3300 BCE (about 5300 years BP, before present) arose a group of people who in essence combined these technological advancements to their advantage. These are what we may call the Proto-Indo-Europeans. They may or may not have been the first people to develop each of the technologies in question here, but they integrated them effectively, very effectively.

Here’s a somewhat simplified, even simplistic, account of a summary of what most likely happened.

The PIE-folk, being inhabitants of vast grasslands, master horse-riding, and combining that with the wheel, build a functional and practical form of early wagons.7 Using bronze they craft weapons, which are far more effective than those of those who didn’t - because bronze broke bones better than sticks and stones! And with the power and mobility this gave them, they spread out far and wide from their homeland.

This can be symbolized in comparative linguistics using their word *kʷékʷlos,8 the name for an object, derived from a verb *kʷel- meaning “to turn”. Let’s trace its evolution, i.e., following the peculiar sound changes it underwent, via 3 different paths to 3 words we recognize (don’t worry about the special signs in the notation):

*kʷókʷlos > kŭ́klos ‘cycle’ (Proto-Hellenic → Ancient Greek)

*čakrá- > cakrá ‘chakra’ (Proto-Indo-Iranian → Sanskrit)

*hwehwlą > hwēol > wheel (Proto-Germanic → Old English / Anglo-Saxon → English)

So remember this when you’re trying to focus on your chakras doing yoga on your bicycle, that thing with two wheels!

(The Ancient Greek and Sanskrit words also mean “wheel” in those languages, which we have been adopted into English with slightly different meanings, and in the case of ‘cycle’, coming to us via Latin, some significant change in the pronunciation as well!)

The Proto-Indo-Europeans are Coming!

But going back to the story of the Proto-Indo-European expansion, there are a few more details we need to get into to substantiate this, including a few other factors that came to their advantage. Let’s explore these briefly.

Apart from the horse, we’ve discussed domestication of other animals, such as the dog and the cat, but we skimmed over a few other more economically relevant animals. No more skimming, let’s go full-fat now! Yes, you guessed it, I’m referring to cattle, sheep-goats and suchlike. While such animals had already been domesticated even before our current story begins, the people we call Proto-Indo-Europeans developed a new capability.

To understand this, we have to once more mentally position ourselves to imagine the state of affairs before such a development. We all know that milk is the staple diet of the newborn of all mammalian species. What we’ve probably not given much thought to is that it’s perhaps uniquely humans that consume milk into adulthood. In fact, that’s not fully true. Even humans have genetically evolved to consume milk only as babies, and this is still the case with vast swathes of the human population.

The key innovation I’m referring to is that the Proto-Indo-Europeans adapted to the consumption of milk products as adults. There has been a debate as to whether this was facilitated via a favorable genetic mutation allowing for lactase persistence, the ability to digest milk in adulthood, but given this requires extensive discussion, at this stage, let’s proceed with the fact that they adapted to extensive consumption of dairy products, whether directly whole milk or just its derivatives such as cheese and yogurt.

In an age long before the advent of refrigerators this gave them a sort of ‘refrigerated food storage’ in their long-distance ventures: they could carry their cow and sheep with them in the wagons and get milk/dairy on demand, allowing them to move across vast areas rapidly.9

The Urheimat

The other big question is of course where did they come from?10

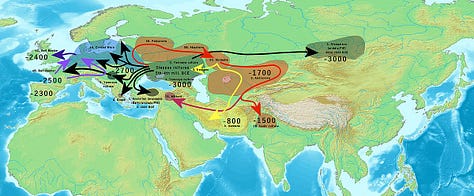

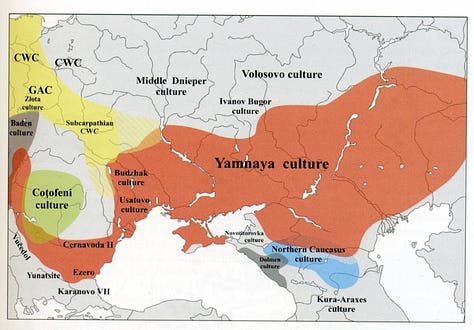

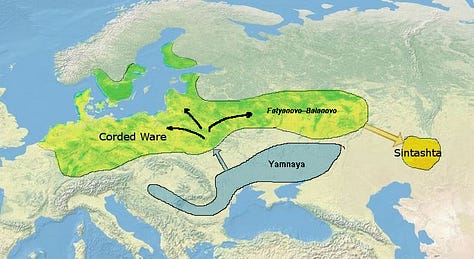

The Proto-Indo-European spread has been associated with the emergence of this people starting about 5300 years ago in what’s called the Yamnaya culture in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe broadly stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (Pontus Euxinus in ancient times) to the area north of the Caspian Sea, all north of the Caucasus and part of the wider Eurasian Steppe - dark green in the below map, the light green denoting the full expansion.11

With their horse-driven wagons and livestock and all the advantages I’ve outlined, they were able to rapidly move across the vast Eurasian Steppes and eventually beyond. Inhabiting the vast grasslands, they lived, at least initially, a semi-nomadic lifestyle, settling in one makeshift location and moving on, probably with the change of season12 and/or depletion of grass in the vicinity essentially for their horses and cattle and thus for their whole livelihood.

You have noticed that the bulk of the treatment here is on the basis of linguistic rather than archeological or genetic studies. There are at least two reasons for this. Firstly, it’s the linguistics bit that kicked off much earlier, like I said going back 200 years now.13 Because they were a semi-nomadic people they haven’t left behind as much by way of material remains for sufficient and satisfactory archeological analysis, at least relative to the wealth of linguistic data that we have. Furthermore, the growth in the area of genetics has been even more recent, as recent as the last 5-10 years, compared with the 200+, given only recent availability of ancient genetic material or the instrumentation and technology to analyse such specimens.

In later stages in this series, when we discuss the development of these other disciplines, especially genetics, I expect to have more to say on some of this from those angles. But suffice it to say at this stage that the methods I’ve only briefly touched upon already throw light on this fascinating phenomenon.

Loud and Clear

I have given just one or two examples of ‘linguistic fossils’ as part of our ‘verbal archeology’, but I can give you thousands of words, words of everyday use, not just in English, but equally so in Portuguese or Persian, in Lithuanian or Lom,14 in Bengali or Breton.

By scrutinizing the evolution of such words into the Classical (Latin, Greek, Sanskrit) and the vernaculars of our own time, we can trace, with astonishing revelatory power, some of the core ideas, beliefs, notions of these people and how they left a mark upon us in far more ways than we could imagine. There have been many books written about such detail and I’ll enumerate just a few of them below with my personal assurance from experience that they all make for great reading. Here however, I’ll give one other example that hopefully makes my point:

Like many other ancient peoples, the Proto-Indo-Europeans had a notion of ‘glory’, ‘fame’, which manifested extensively in their poetry. Being a pre-literate people, their word for this idea is related to the sense of hearing. Again this word has undergone a bunch of sound changes in the different daughter languages, but we can trace it by capturing this evolution, as we did above. So let’s play verbal archeology one more time!

The PIE word for in question is ḱléwos from the root ḱléw- “to hear”.15 Observe:

kléwos → kléos (Proto-Hellenic → Ancient Greek)

ćráwas → śrávas / srauua (Proto-Indo-Iranian → Sanskrit / Avestan)

ślawas / ślṓwā → slava / slovo (Proto-Balto-Slavic → Slavic)

klutom → cloth / clod (Proto-Celtic → Irish / Welsh)

hlūdaz → laut / loud (Proto-Germanic → German / English)

As you can see, over a 5000-year period, this ancient word for “fame”, “renown” still lives on. In myriad forms hard to recognize without a bit of specialist training in a field representing two centuries of rigorous scientific enquiry, which I have condensed for you in the space of this one article.

Most of the final forms of that word showcased above (and for practical reasons I’ve skipped a few dozen other derivatives from the same root!) retain the meaning of ‘fame’ in the sense of ‘heard far and wide’.

But often they extend the meaning, such as the Slavic ‘slovo’ or Avestan ‘srauua’ “word”; the Sanskrit forms such ‘śruti’ connoting ‘revelation’; the Greek form being seen in a great many famous names, such as ‘Peri·kles’, ‘Hera·cles’ and indeed, ‘Cleo·patra’! The Slavic forms indeed go on to give that very people their name, even as they sought ‘slava’ “fame”! And finally, the Germanic form can still be heard.. ‘loud’16 and clear. You just have to.. ‘listen’!

Listen a bit intently for, as I said at the end of my story of the horse, the Proto-Indo-European story is

a tale of imperishable fame that’s gathered dust since the mists of history, a song of latent legacy needing resung, the most far-reaching of all of our horse-mounted triumphs; one that spans continents, one that stretches millennia, one that lives on in thousands of words we use every single day!

Gallery

(The following animation and images illustrate the Proto-Indo-European homeland, spread across the Indo-European expanse, and the tree of languages descended from Proto-Indo-European. Click to enlarge and view.)

Further Reading

(The following is a subset of the sources that have shaped my understanding of the subject matter in this and related fields as part of my study going back 30+ years. There are some books here I’ve devoured end to end, but I’ve read them all enough to recommend them, with the caveat that some of the archeogenetic material might be somewhat dated given the still ongoing findings in this area. Happy Reading!)

Anthony, David W. (2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400831104. (Complete text at archive.org)

Fortson IV, Benjamin W. (2010). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. 2nd Edition. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1405188968. (Complete text at archive.org)

Mallory, J.P & Adams. D. Q. (2006). Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199287918.

Watkins, Calvert. (1995). How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195085957.

Beekes, Robert S.P. (2011). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. 2nd Edition. John-Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9027211866.

Clackson, James. (2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521653671.

Benveniste, Émile. (2016). Dictionary of Indo-European Concepts. Hau Books. ISBN 978-0986132599.

Parpola, Asko. (2015). The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-019022690-9.

Reich, David. (2018). Who We Are and How We Got Here. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198821250.

Mallory, J.P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archeology and Myth. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0500276161 (Complete text at archive.org)

Jamison, Stephanie W & Brereton, Joel P. (2014). The Rigveda: the earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199370184.

Monier-Williams, Monier, Sir. (1899). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with special reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Oxford University Press.

Pāṇini. (±499 BCE). Aṣṭādhyāyī. ISBN 0-0.

In some ways displacing the older disciplne of ‘philology’

Our general notions of language as daily users of it can be rather different, even distorted, compared to the scientific study of it, so it helps for us to suspend some of the more popular folk notions if to get the best out the scientific perspective

That, writing is an ‘add-on’ technology, I’ll come back to this I promise

The Latin word for male was ‘vir’ as seen in the derived English word ‘virile’

‘fu’ shows up in the word ‘future’: sort of like ‘will be’

This has the same scientific rigor as any other including its predictive power. As an analogy, the presence of Neptune had been mathematically predicted as a planet many years before technology developed good enough instrumentation to actually empirically prove its existence

The early wagons were ox-driven

The preceding asterisk is a suggestion in the notation that the word hasn’t actually been attested in literature

Another aspect that has been associated with their spread, which also requires more genetic scrutiny I won’t get into at this stage is that, having lived in close proximity to animals - their cattle, sheep and other mammalian types, they developed immunity to animal-borne diseases, which other populations did not have. This might have given them an advantage, similar to when the Spanish and other Europeans arrived in the Americas, carrying within their immune bodies or livestock germs which the hapless natives had no immunity against.

The technical term in historical linguistics for a proto-language origin is ‘Urheimat’

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8d/Indo-European_steppe_homeland_map.svg

The RigVeda, composed by their Indo-Aryan descendants in the centuries around 1500 BC, describes some of these seasonal movement patterns they’d still retained

The German linguist Franz Bopp and his pioneering work around Sanskrit and building up the comparative field in the early 1800s deserve a special mention

Or ‘Rom’ the language of the Romany/Gypsy people

The last two examples in the list deriving from a slightly different form of the word

A famous Germanic name being ‘hlūd·wīg’ “loud in battle”, the source among others of ‘Clovis’, ‘Lewis’ and ‘Louis’

It was an enriching read. You convey the passion you feel for these topics. You explain it in very simple detail so that people like me can understand it. You have a wonderful mind. Good work.

This is the kind of techno-history I’m here for: what got invented, AND why it stuck. Such a great deep dive, I can only imagine the effort this took. Thank you for sharing🤗