TecC 37 - Finding the Medium: Turning the Page

The substrate of progress: making knowledge growable, storable, durable and shareable

You might have realized reading the last few articles that they have been heavy on the question of intellectual activities and achievements, perhaps more so than in the previous decades of our treatment (until Episode 30). But we have to talk about the very medium that underpins a good part of this progress.

First let’s see what our fictional friends are up to.

Steve and Bryan are sat at the table looking rather worried indeed. The Kingdom is at war with a neighboring one, but the worst part is that that kingdom has been the supplier of the materials that make up the writing medium. This supply-chain crisis is threatening to have a knock-on effect on everything here.

Steve and Bryan have been at the service of the local Duke, Steve handling copious amounts of record-keeping around the bureaucratic apparatus and Bryan managing crucial tax and accounting records. And now, the additional demand of maintaining war logistics could have further augmented their income, but for the dwindling of the very resources they need for all this.

The writing is on the wall (well, no that’s not the medium of in question here, but stick with me!) - either they find a way of fixing this problem, or lose their jobs, perhaps everything. And this is urgent. The Duke has a high regard for our friends but that only means more expectation and correspondingly more disappointment if they don’t turn things around.

So Irene and Brenda turn up, and are like, guys, what’s the matter?! From your faces, it looks as if the sky is falling? But, once they come to know the gravity of the situation, they join the lads determined to find a solution.

It’s now their third session in three days, they’ve been brainstorming - discussing all sorts of potential solution, smuggle the precious raw material from the enemy kingdom? Nah, too dangerous. Maybe hire mercenaries to do so? Still, murky waters. Maybe invent a new medium? But how?

And suddenly Brenda notices Irene has been fidgeting quite a bit. She’s like, what’s that hanky you’re playing with Irene. She takes this white piece of cloth from Irene and she’s like, why’s this so stiff and weird?

Bryan is furious, come on Brenda, we’re about to lose our livelihoods, and you are curious about what Irene’s got in her hands. Steve bursting out, and you Irene, playing with useless stuff while we’re trying to solve this problem, it’s do or die.

But Brenda is still feeling out the hanky with curious looks on Irene who’s finally like, well, Iris the cat was rolling on it, so it’s become somewhat stiff and starchy. Brenda is then like, hold on, can we scribble on this, pulls out a quill, tests it. All goes quiet! Wait, is this it??

And then Steve is like, come on Brenda, this is just a piece of rag that Iris rolled over on. Are you saying our cat is going to become the manufacturer of a new writing material? This is downright silly! But Brenda is unfazed, she’s like, you know what, this texture, the flatness, the stiffness, feels just like what came of that pulp of leaves I saw out in the garden. Bryan is like, the leaves that were soaking in the puddle? Nonsense, what’s some wet rotten leaves got anything to do with this! This is totally gross!

But Irene now adds, oh yeah, that pulp then dried out in the sun which was particularly fierce this week? Brenda going, exactly, and then our dog Bruno was rolling all over it. That was actually after Bruno dragged it next to the fireplace. It kept rolling over... wait, let me get it, right here... so we can make this ourselves, in bulk... leaves in pulp, heat, flattening, more working... look, I can write on this Bruno-roll just as on Iris-roll, we’re on a roll! Many rolls!

Pulp Fiction to Plain Fact

Right, so this of course is paper! But the real process here took centuries to pan out. In fact, just as we saw in Episode 28 how the zero-based number system we use today developed only in Ancient India, so also paper as we know it developed in only one culture, Ancient China.1 And just as it is easy for us to take for granted the value of the Indian numerals, so it is with paper, because they’ve both so intrinsically become a part of our life. I now wish to demonstrate the value of paper, why it was an innovation on multiple fronts: give me a chance to make my case, a whitepaper if you will!

Paper come to be of widespread use in Europe only after the year 1000. But there was paperwork, I mean work on making paper, way back in China. The traditional attribution is to an imperial eunuch named Cai Lun in the year 105, but archeological investigations have revealed that they were working on early forms of paper in China even in the couple of centuries before the turn of Era. Cai Lun in fact made its production systematic and obtained royal patronage to transform it from a niche to “a mass-produced commodity”.

This key transformation happened during the Han dynasty, one of the most formative and important periods in Chinese imperial history. Prior to this, the main medium of writing in the Far East, as we can imagine, was Bamboo, but paper was a huge material improvement as I’ll demonstrate shortly.

Papermaking to Paperwork

Another huge milestone in the history of paper takes us to the later Tang dynasty, roughly three centuries from about the year 600. The Tang empire expanded on an elaborate system of bureaucratic recruitment, a key component of imposing centralized, top-down control on the masses. And the cornerstone of this was the examination system, (a hugely important and consequential institutional innovation which merits a separate full article of its own - watch this space), which as the name hints, involved subjecting large numbers of candidates to exams in order to qualify for imperial bureaucratic service. (The pass rates of 1-2% suggests massive candidate volumes.)

It’s not hard to imagine how this is intimately bound to the availability of large quantities of a cheap and easy-to-manage writing medium. The economics and logistics of such a large-scale operation would just never have been possible without something like Bamboo - we’re talking hundreds of thousands of candidates annually! (”Right, we have 112,245 candidates this year, how many bamboo forests do we need to clear, minister?” “Well my lord, all of’em!”)

And then, beyond entering the civil service, there’s all the paperwork in administering the whole empire.

Leaked Papers

It is said the Chinese fiercely guarded the secret of papermaking. But there are limits to how much and how long innovation can be kept hidden, be it by a centralized authority or inward-looking forces. The flashpoint in the story is the Battle of Talas fought in Central Asia in 751.

We saw in Episode 32 and in Episode 33 the rise of the Abassid Calphate as part of the emergence of Islam as a potent military force, and under the Abbasids, the Golden Age of Islam roughly the five centuries from 750.

The battle was fought on the Talas river (present-day Kazakhstan/Kyrgyzstan) between forces of the Tang dynasty and the Abbasid army, leading to a victory of the Abassids. The story goes that the Abbasids got a few of the Chinese prisoners of war to show them the secret of papermaking. (I mean, hiding the secrets of papermaking is harder than swallowing a piece of paper with secrets in it you say?)

However, although this makes for a neat story, this has been largely discredited by modern archeological and other investigations. Paper had been used in Central Asia even before that pivotal battle.

At Crossroads

Let’s pause to look at this place a bit closely because it’s an extraordinary story we have sadly forgotten. For many centuries before this date, Central Asia had been a large, highly populated and urbanized thriving civilization (The Greek geographer Strabo in the last century BCE calls it ‘a land of 1000 cities’). The population was highly literate, numerate, and cosmopolitan.

A notable section of the population was Zoroastrian, but the Buddhist presence was even more pronounced especially the further East you went. There were also Greek settlements pre-dating Alexander with the Hellenistic elements accelerated after his conquests. And then there was a notable Christian (or specifically Nestorian) community (one of whom we met in Episode 33), with all of them living in an atmosphere of religious tolerance, free thought and expression, including ideas of atheism and skepticism.

The Middle Way

Of all these, Buddhism is said to have played a foundational and transformative role in the intellectual and material culture of Central Asia prior to the Arab conquest, in particular in the sphere of literary matters, establishing a tradition of textual scholarship over the course of a thousand years before the rise of Islam.

Thus we can see that there was a Golden Age of Buddhist-drived Central Asian culture that lasted about a millennium before the pivot in 750. (And thus meriting another spinoff in its own right which also I intend to come back to in the future.)

And as part of this highly fertile intellectual, literary and religious Buddhist environment, which in significant part involved a large amount of intellectual exchange between India and China, or from India to China, including copious amounts of translation of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit and Pali into the Chinese and other languages, it has been found that paper was a key component.2

751 was thus a turning point mainly militarily, in that with the Abbasids victorious, they were able to impose their rule and religion on what we know today as the stans. The focal point, from the perspective of the paper story, is Samarkand which emerged as the key center of paper production, and the Abassids made further innovations to industrialize papermaking.

And it was this in fact that enabled the Islamic Golden Age which I’ve already covered in depth in Episode 33, and how from there, on the fine medium of crisp paper, all their knowledge moved to Latin Europe via Muslim Spain, which also I’ve detailed in Episode 33B. And then, just as we saw in Episode 28 how Europe was resistant to adopt the Indian Numerals with the Zero, it took a few centuries of European resistance before paper became widely used in the west.

A New Chapter

So now let me address the question of what the big innovative leap paper was, and to do that we must pause to look at the previous alternatives.

In Episode 16 when I discussed the invention of writing, and in related pieces such as Episode 24 we saw that some of the earliest writing was on clay, specifically cuneiform letters wedged onto soft clay and then baked to harden. We saw in Episode 20 and Episode 21 how this method largely disappeared with the collapse of the Bronze Age, in western Eurasia.

In the Classical period, when writing made a comeback in an entirely new way, as we saw in relation to Episode 23, this was done mainly on Papyrus, its source originating almost solely from the Nile Delta in Egypt. It’s not hard therefore to imagine the monopoly Egypt had on this material during Classical Antiquity. In fact my fictional story above indeed has a historical precedent when Ptolemaic Egypt banned papyrus exports to rival Pergamon.3

Thus in the early years of the Christian era, Europe began to move to another alternative - parchment, or vellum, which was made out of animal skin. This was the main medium all across Christendom until the eventual adoption of paper.

In China itself, there was a tradition of writing going way before the advent of paper as we saw above. Prior to paper, Chinese writing was done on Bamboo, wood strips or even silk.

Finally, in South and Southeast Asia there was writing based on palm leaves which were stitched together. (The Sanskrit word sūtra is in fact literally the same as the Latin sūtūra, our ‘suture’: a sewing, stitching!)4

The Tricky Trilemma

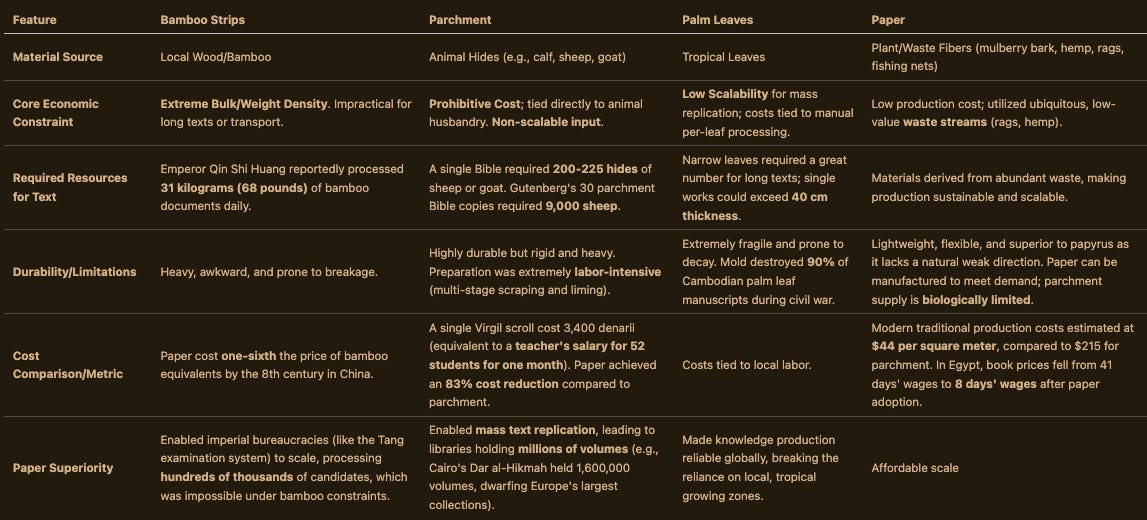

The problem with all these alternatives is this. Out of the qualities of affordability (cost), portability (lightweight) and durability (resilience), each of these other writing mediums only provided two at most.

Bamboo while convenient, is extremely bulky and thus not viable for large volumes of writing

Papyrus as we vividly saw is (or was) extremely geographically limited

Palm leaves, while very light, has massive problems of durability, it’s significantly less long-lasting and prone to mold and rot compared to the others.

Finally parchment, while durable, was extremely expensive. Furthermore, being made of the hides of sheep and goat, it was not only massively resource-intensive but thus also hugely environmentally and ecologically questionable.

Cheap and Cheerful

Paper happily solves all these problems. It’s not bulky like bamboo or parchment. It’s more durable than palm leaves and, if well made and kept, than papyrus. It’s not as resource-intensive and expensive as parchment.

But here’s the thing, the making of paper is a bigger innovative leap than these others. It’s not obvious, as we can imagine and I hope I’ve demonstrated, that it’s possible to get to a material like paper from a bunch of rotten plant matter soaking in water - pulp. It actually took centuries of incremental innovation, first in China, then in Samarkand and the wider Islamic world including Spain, and finally in 1200s Italy.5

All this amounts to significant technological progress in material, chemical, and mechanical fields, and in so facilitating, also a fundamental institutional innovation. Paper is perhaps a classic example of my paradigm of technocentric progress where I define “technology” as both artefactual and institutional.

Let’s have a quick comparison especially from an economic and ecological perspective how much this matters.

So let’s see what we can put on paper.

The development of a vast bureaucratic state making for the establishment of the vast imperial might of China - paper.

The centuries-old flourishing of a vast body of Buddhist intellectual, literary and religious activities as part of a Central Asian Golden Age, in the corridors between India and China - paper.

The succeeding years of the Islamic Golden Age and its transmission to Latin Europe - paper.

Guess what, we haven’t even touched upon the biggest story of this all - I’ll come to it in Episode 42!

But for now let’s think about this. As I’ve said, it’s easy to take something like paper for granted. Furthermore, we have in some sense now gone past the age of paper you might say, with our lives increasingly lived in a digital world. But paper stands at the cornerstone of the bulk of human intellectual achievement, at least in the last 1,500 years if not more?

But even as we may feel we are ready to consign paper to the wastepaper basket of history, what is the durability of our modern mediums? The stuff we have in our smartphones and computers, on flashdrives and harddisks?

Is our data on silicon also just writing on sand?

Is our digital medium our strength as much as our greatest weakness? (Remember the Bronze Age which collapsed suddenly and catastrophically when they couldn’t source tin?) Picture this hypothetical scenario: a single meteoric static boom, of a physiochemical-electromagnetic composition not known to us on Earth at a stroke erases all digital storage.

Is our modern store of knowledge a digital Library-of-Alexandria fire waiting to happen?

Article written by Ash Stuart

Images, voice narration and some footnotes generated by AI

Further Reading & Reference

Wood, Michael. The Story of China. Simon & Schuster.

Starr, Frederick S. (2013). Lost Enlightenment - Central Asia’s Golden Age. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15773-3.

Mortimer, Ian. (2022). Medieval Horizons: Why the Middle Ages Matter. Vintage.

Al-Khalili, Jim. (2010). The House of Wisdom. Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1101476239.

Dalrymple, William. (2024). The Golden Road: How Ancient India transformed the world. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1408864418.

The Mayans independently developed a bark-paper called amatl (or huun) from fig tree bark, used extensively for codices recording astronomical, calendrical, and religious knowledge. However, this bark-beating technique differs fundamentally from the Chinese pulping process that created true paper from macerated plant fibers. Only four Mayan codices survived the Spanish conquest. Similar bark-paper traditions existed across Mesoamerica.

Xuanzang (c. 602–664), recognized as one of China’s greatest scholars, travelers, and translators, embarked on an epic seventeen-year, 6,000-mile overland pilgrimage starting in 629 to resolve contradictions and errors he found in existing Chinese Buddhist literature. He traveled illegally to the Western Regions to reach the intellectual heart of the tradition, seeking out the great Indian university-monastery of Nalanda.

There, he studied texts and copied out manuscripts, especially those related to the Yogacāra school of Mahayana Buddhism, under the Venerable Shĩlabhadra. Upon his return to the Chinese capital of Chang’an in the year 645, he brought back a substantial collection, totaling 657 books bound in 520 cases of rare Indian texts. With imperial patronage, Xuanzang established a Centre for Sūtra Translation, where he and his team produced translations of 74 different Buddhist texts, resulting in over 1,300 scrolls, surpassing the output of his famous predecessor, Kumārajīva. His journey and subsequent scholarship profoundly transformed Chinese religious and intellectual life.

The English word “parchment” derives from pergamenum (Latin) and pergamēnē (Greek), literally meaning “from Pergamon.” According to Pliny the Elder, when Ptolemaic Egypt banned papyrus exports to Pergamon in the 2nd century BCE to prevent the rival library from surpassing Alexandria’s collection, King Eumenes II of Pergamon developed parchment as an alternative writing material. While animal skin had been used earlier, Pergamon is said to have refined the production process—treating, stretching, and scraping hides to create a superior writing surface. This innovation broke Egypt’s papyrus monopoly and gave the city its enduring association with the material.

Many words for books and writing surfaces derive from their physical construction or material. Codex comes from Latin caudex (tree trunk, block of wood), referring to wooden tablets bound together. Volume derives from Latin volumen (scroll), from volvere (to roll). Bible traces to Greek biblion via byblos (papyrus), named after the Phoenician port city Byblos. Latin liber (book) literally means “bark, inner bark of tree.” Page stems from Proto-Indo-European peh₂ǵ- (to attach, to fasten), reflecting the binding of sheets. Even book itself connects to Old English bōc and the beech tree, on whose wood Germanic tribes inscribed runes.

The library of Córdoba held 500,000 books in the 900s. Libraries in Cairo, Baghdad, and Córdoba held collections that included up to 1,600,000 volumes by the year 1171. Concurrently, the largest European monastery library in the 9th century held 36 volumes. A single scholarly monk in Europe, Bernard of Chartres, was noted for owning as many as twenty-four books! The Abbey of Cluny, a major intellectual center around 1085, possessed a few hundred books.

200 books for the whole city... and still enough to dream and remember.

The beauty is in this care. Digital books have made knowledge enormous in volume but incredibly fragile. Very interesting article, Ash!👏

My son was recently telling me about how people in ancient China actually died from some state examination?!?! (Though from what I hear from relatives, the current high school exams are probably just as gruelling 😅) And I believe this is the one you’re referring to here? Would absolutely love for you to write about it!!

Your question at the end kind of jolted me. I’ll admit that after learning about the heavy reliance on oral traditions by ancient cultures, I went “you guys didn’t think to write this stuff down”? And now, I’m wondering whether those in the future will look back at us and think “seriously? You guys just stored stuff on the cloud?!” 😅